by Erika Solberg

One obvious and important way that VAMPY classes differ from classes at school is that students do not receive any grades. Without grades, students do not need to worry about their GPA or competing for the best class standing — they can take risks knowing that neither success nor failure will have a long-term impact on their academic status. They also do not have to worry about performing to please a teacher, meeting a state mandated benchmark, or chasing after an interest that veers away from class lesson plans.

This shift away from traditional assessment methods can be uncomfortable at first for students who are accustomed to monitoring their progress and making sure they are “doing it right,” but it ultimately creates space for learning that focuses on growth rather than predefined achievements, and on passions rather than test performance. As Physics student Ellen Sego of Glendale says, “I get to learn without the worry of keeping some arbitrary grade — I can focus on getting what I need out of the class rather than getting what other people want me to get out of the class.”

VAMPY students tend to end up loving the lack of performance pressure in their classrooms, but if there are no grades, no exams, no benchmarks, no ratings of “proficient” or “distinguished,” how do we know whether or not VAMPY classes are worthwhile? How do VAMPY teachers know that students are learning?

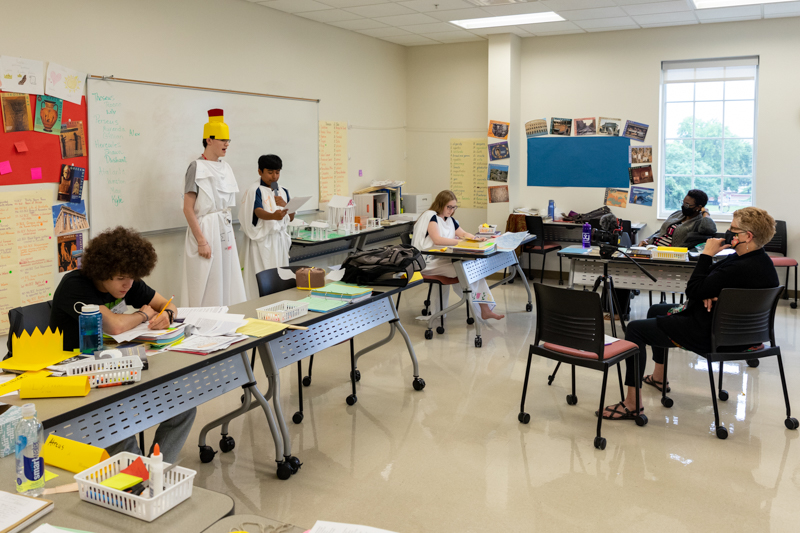

To begin with, many classes employ student presentations where students synthesize and apply what they have learned. For example, in week two of Ancient Civilizations, teacher Jan Lanham of Gravel Switch had her class create presentations on famous battles in the style of modern TV news. Alex Minter of Bowling Green and Shawn Cochran of Hendersonville, TN, reported on the battle of Marathon while incorporating paper helmets, changing roles, and humor. First Alex interviewed Shawn as he portrayed Athenian general Miltiades, who asserted, “My army was assembled in haste!”

Next Shawn switched to the role of Pheidippides, the Athenian messenger who ran 26.1 miles to report the news of a Persian defeat and died on the spot. “Oh, my gods!” Alex shouted before interviewing the ghost of Pheidippides, to whom he offered a coin to cross the river Styx.

After several more role changes by both students, Jan asked the class, who had filled out evaluation sheets during the presentation, what Alex and Shawn had done well. She also gave the presenters her own immediate feedback and asked the whole class to discuss why the battle was significant. The presentation format required students to stay engaged, demonstrate knowledge of facts as well as analysis, work on public speaking and creativity, and share ownership of teaching and learning in the classroom.

Presidential Politics also makes use of presentations, especially with its daily mock presidential debates. As they study American presidents from 1960 to present, students take turns roleplaying the candidates in their historical debates. This exercise asks them not only to know where the candidates stand on major issues and to be familiar with current events of the time but also to take that knowledge and use it in spontaneous arguments. Teacher Dennis Jenkins of Bowling Green explains, “They have to think on their feet because they don’t know what their opponent is going to say, especially during rebuttals. They also have to be flexible in their thinking because they may have a different opinion than the person they are role-playing.”

On Tuesday during the third week of VAMPY, Jayden Shuai of Portland, OR, and Alex Ladd of Scottsville portrayed Barack Obama and John McCain during a 2008 debate. After giving opening statements that focused on their candidate’s background, they answered questions from Dennis and TA Josh Young of Bowling Green on their choice of vice-president, the war in Iraq, the economic crisis, and McCain’s appearance on Saturday Night Live. The highlight of the debate came during an extended back-and-forth on the bank bailout passed by Congress in the waning weeks of the election. Their sparring allowed Dennis to observe how much they had learned as they conveyed facts they had acquired in different contexts.

In Writing, teacher Audrey Harper of Bowling Green uses a specific presentation format called Pecha Kucha at the end of the second week of class to help students master the area in which they are doing their course-long multi-genre, multi-modal writing projects. The presenter gathers twenty images related to their topic into a slide show in which each slide is displayed for 20 seconds, and they have to speak about each slide for the whole time it is displayed. Audrey explains, “They’ve been doing research on their topic for two weeks and now have to synthesize it and share information. It’s a forced form that many of them are not familiar with, and it breaks them out of the ‘PowerPoint Karaoke’ style that a lot of students are accustomed to where they show slides full of text and then just read the text. It forces them to come up with the words and speak in a more impromptu manner.”

In her Pecha Kucha, Grace Fridy of Lexington spoke on her topic of violence against women in the military, focusing on military sexual trauma. Many slides showed statistics as she discussed the low conviction rate and information about the effects of trauma. In contrast, Sydney Schulten of Fayetteville, GA, used illustrations from the Harry Potter books and stills from the movies to present her argument that the character of Draco Malfoy is misunderstood. Despite the very different topics, the presentation format allowed both students to assess their level of knowledge on and ability to speak about their area.

Audrey has several other methods in her class to help students track their learning. She has her students set goals for themselves on the first day of class for what they want to learn and has them check in on their progress throughout the course: “This class is tailored to what they want to get out of it. Today I said, ‘Let’s look back on some of your goals: where are you? What have you done? What do you still need to do to reach those goals? What can I do to support you?’” Students also do a student reflection at the end of the course that asks them about key class activities such as Reading Like a Writer and their Critical Friends Group, which provides feedback throughout the course on their writing.

TA Christian Butterfield of Bowling Green, who is also an alum of the VAMPY Writing class, says these assessment methods are designed to get students out of any rut they have gotten into at school: “This class differs a lot in evaluation from traditional instruction in that we’re not meeting a specific benchmark — rather, we’re measuring their growth. You can come into this class as a Pulitzer Prize winner or as an un-confident writer, but what we care about is seeing your growth from the first day of class to the end of your multi-genre product. That type of evaluation challenges the students to reconsider their work beyond the objectives of making a certain score or making a certain grade.”

The Problems You Have Never Solved Before class covers a different discipline than the Writing class, but it too takes advantage of the lack of grades to push students in their learning. Teacher Catherine Poteet of Bowling Green intentionally does not provide students with clear blueprints for solving the problems she gives them, be it building a catapult so a marshmallow hits a target on the floor or figuring out the next number in a sequence. She says, “During the first week, a lot of them ask, ‘What’s the best way to do it? What do I need to do?’ It takes about a week before they realize I’m not going to tell them. At first some students get frustrated because they are used to doing things the way the teacher wants so they can get the grade they want.”

It is ultimately their growth in creative, independent, out-of-the-box thinking that she assesses, and it is not just their solution that she looks at but their thinking process: “They have notebooks where they write out their plan for their project and why they think it’s going to work so I can see if they’re following an engineering design process. Then they gather the materials, build it, test it, and describe their results in their notebook. Did their plan work or not? Why?”

On the second Thursday of camp, Catherine introduced a new project, a straw rocket made from wooden skewers, colored duct tape, a plastic straw, and a rubber band. It was an unusual project in that she guided the students through the initial build (which is why she saves it for the second half of the course). However, this process was only the first step: they then tested their device, collected and analyzed data, and modified their build. That second build is what sets the class apart: “One thing we get to do in here that they don’t get to do in a regular classroom is rebuild — not just write down what they learned and what they would do differently if they built it again but to actually build it again.” It is in the trying again that much of the learning take place.

Like the Problems class, VAMPY Physics is about more than learning concepts. Teacher Kenny Lee of Bowling Green in Physics wants his students to learn concepts, but he also wants them to “appreciate the topic. Physics has a reputation of being hard and difficult, but it’s really not — it’s just thinking about the world around you. I want them to have an appreciation for it and for the wonder of the science.” For those reasons, he does not worry about the “constant repetition and drill” that might need to happen in a school physics course. He says, “We hit a topic, discuss it, go through it, and go onto the next topic. Whatever they absorb, they absorb. They might miss things sometimes, but that’s okay. If they take physics later on in school, they can fill in the gaps. Our course is more fast-paced — and it’s a lot less stressful.”

Besides assessments at the end of each week that help him “gauge how much they absorbed,” Kenny tracks students’ learning by asking questions and checking their work in class. Additionally, in evening study hall, students do problems sets with their TA, Chloe Jones of Bowling Green. She says, “The students are able to do them without much guidance, and if they do need guidance, it’s just help with a conversion or reminding them of an equation. They’re able to do the work and talk it through with me.”

Kenny does demonstrations as well that help students apply and appreciate concepts. On Monday of week three, he built on their knowledge of electromagnets by demonstrating a music speaker made from a coil of wire, a magnet, and a Burger King cup — he called it “the king of speakers.” Next he showed them a metal rod with current that alternated 50 times a second. He put a small metal cylinder onto the rod and held it there, asking them what would happen when he let go. Ibrahim Ali of Bowling Green correctly predicted that it was making its own magnetic field and would therefore fly off. Kenny asked for a volunteer to catch the cylinder, and the class unanimous volunteered Corey Coleman of Berea. As Corey prepared, hands out, knees bent, Kenny paused to tell of the time that he did this demonstration and the student who was supposed to catch the cylinder instead took a hit right between the eyes — “and he never stopped grinning!” Corey, fortunately, caught the cylinder easily.

Class discussion — without the flying cylinders — is a method used by DNA and Genetics teacher Colton Isaacs of Alvaton as well. He says, “I can gauge a lot about student understanding by listening to them talk to me and with one another.” He also likes to have the whole class review concepts together by asking them what they know and listing their answers on the board: “As they talk and I write their responses, they make connections.” When he does do assessments, he sees them as “a general gauge of where students are at and how much they absorbed and retained,” meaning the assessment is as much for him as for them.

Colton finds this approach overall makes students “a lot more comfortable. They feel like they can express themselves in ways that maybe they can’t in a traditional classroom setting. They’re not scared to ask questions that they might otherwise feel would be ‘dumb’ questions or wouldn’t directly apply to what we’re learning. It gives them the autonomy to think outside the box and hopefully appreciate and love the science.” Without tests or labs that count towards a grade, students are free to go where their learning and interests take them.

Math is probably the most test-heavy of the VAMPY classes because many students are hoping to earn high school credit for what they are studying. However, teacher Natasha Gerstenschlager of Bowling Green says that despite the tests, Math still uses a no-pressure approach: “Students take ‘traditional’ assessments, but they are not high-stakes. If you fail one, you take it again.” The assessment also does not end with the usual big red grade written at the top, either, but rather becomes one step in a three-week-long conversation. Students study material individually since they come into the class at different levels, and when they are ready, they take a test. Natasha grades the work, but then “The student and I have a conversation and talk about any questions they missed. If I notice they did extremely well, I’ll ask them to look at the next couple of chapters in their book, and we have conversations about that material. I had one student who was studying trigonometry, but we realized she was actually ready for pre-calculus. That came from our from our verbal interactions.”

Natasha also pays attention to any persistent gaps she notices in students’ work and addresses them: “When they’re taking assessments or working in class and I see one of those holes, we either talk about it as a group with other students who are studying the same thing or one-on-one so we can fill that gap.” Additionally, when students are doing a daily group project, she can ask them questions and check on where they are. For example, in the second week, students worked with motion detectors by walking in front of them and graphing the data. At one end of the classroom, Carlsen Russman of Louisville ran back and forth like he was doing a shuttle run; at the other end, Kate Harmon of Napoleon, OH, took tiny steps; and in the middle of the room, Natasha asked them questions about the rate of change in their graphs, such as “Over what interval do you see the steepest or the largest rate of change? At what intervals do you see the same rate of change?”

Natasha finds the structure of the Math class works well for the students: “At the beginning, when they realized they had to take tests, they were intimidated, but then they realized they could open a book to look up a formula or ask a friend in class for help. They realized that their individual performance was not being put up against a relative measure — that they were truly assessing themselves.”

Along with VAMPY teachers, VAMPY students themselves can tell that they are learning. For instance, Charley Nanney of Memphis, TN, who is taking DNA and Genetics, says, “At school it doesn’t seem like I’m learning much because everything goes so slowly, but here we’re going through the curriculum really fast.”

Physics student Ellen Sego points out, “I know I’m learning because I’m able to do more advanced material as we go along. Topics build on each other, so if I can do the problems today, then obviously I learned what we were studying earlier.”

And Cristina Tekemska of Cordova, TN, also a DNA student, perhaps captures the VAMPY ethos best when she says, “I know I’m learning because I’m developing new ideas on the topics that we’ve been studying — I’m thinking more about things I have never thought about before.”