by Erika Solberg

Few get to experience The Center’s summer programming from as many perspectives as Torri Martin of Louisville. First, she attended VAMPY in 1990-91; then, her son Max went to VAMPY in 2016 and her son Henry is a 2018 SCATS camper; finally, she is an instructor at SCATS this summer, teaching Radical Rube Goldberg as her practicum for her endorsement in gifted and talented. Her experiences as a gifted student and as the parent of gifted students have greatly influenced her job as a national board-certified eighth grade math teacher in the Jefferson County Public Schools; now, her knowledge influences what she does in the SCATS classroom.

A lot of Torri’s camp memories focus on activities outside of class: “I remember Paper Theater, walking up the hill — and how big that hill seemed — and the talent show. I remember going to Opryland and having those tee shirts that none of us wanted to be seen wearing. I met kids who were like me, and that was a big deal — I met one of my best friends there.”

The social aspects of VAMPY were important because Torri came to camp as a young person whose giftedness made her feel like she didn’t fit in: “I was a very mathematically strong girl, which was not always appreciated or supported in the classroom. I was an oddity at my school.” VAMPY, however, taught her as much about herself as it did about the subjects she studied: “It made me much more confident in who I was as a person, and then that’s the person I was back at school. One of the best things that ever happened to me was being able to say, ‘This is who I am. I’m okay with it, and if I’m okay with it, I’m not too concerned whether you’re okay with it or not.’”

Growing up, Torri’s mother was her best advocate and teacher. When school was not meeting her needs, her mother took action: “My mom was very focused on the idea of ‘my daughter needs to be challenged. My daughter needs to have experiences, so I’m going to find those experiences for her.’ She was a brilliant woman — she was valedictorian of her high school, though she did not go to college and had no background in education. But she found contests, speeches, and classes and would bring them to me and say, ‘Okay, this is your plan.” When I listen to debates now about how girls take a back seat in school, it’s funny because it never occurred to me to do that, because I was raised by a mom who never had in her world view that I would take a back seat to anybody.”

Even with her own experiences to draw on, ensuring that her sons have what they need at school has “been kind of a battle all the way through.” Acceleration, pushing teachers and school administrators to make adjustments, switching schools, testing, and intense enrichment activities have all come into play. The best outcomes have arisen from opportunities for academic freedom and from teachers who “give my sons the space to be who they are.”

This idea of accepting who students are and providing space for them to grow has been integral to Torri’s own teaching. Education has been her second career, and in her five years as a new teacher working in schools where her students have a broad swath of needs and abilities, she always knew that no one lesson plan would work for everyone. She explains, “I realized that in order to be successful with my crazy range of students, I had to differentiate everything I did. So a lot of what I’m learning in the gifted education program is stuff that was doing on instinct already, and now I can put an article or research behind it.”

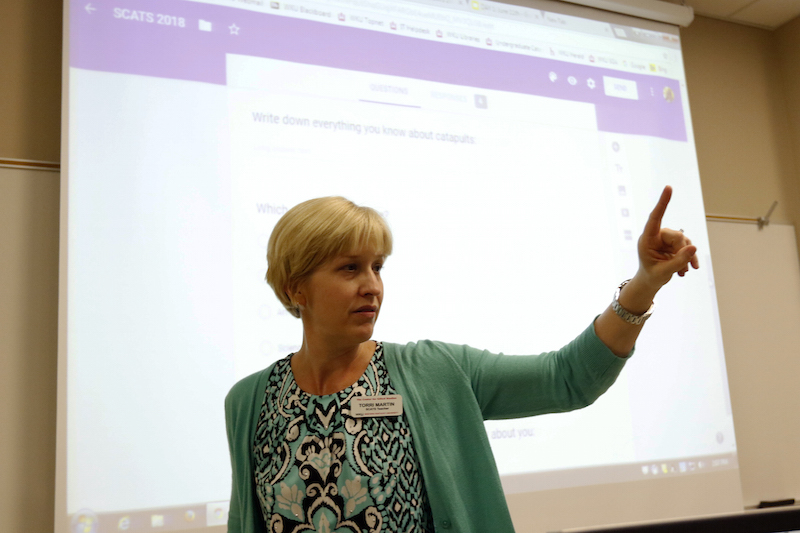

For her class at SCATS, she drew on projects she had done with her middle school students creating marble inclines and catapults. She believed the Rube Goldberg concept — where students build complicated machines to do simple tasks — would appeal to campers of varied interests and “let them play, explore, try, and fail — for a lot of kids, that failure part is really difficult, especially if they’ve never failed before. I also like when they’re given a limitation in terms of materials — they’ve got a complex problem they have to figure out, but beyond that, what they do is up to them.”

Last week, she had teams working on a variety of machines, including one that would start a fidget spinner, one that would turn a Rubik’s cube, and another that would drop a toy monster into an abandoned building. Supplies included Legos, empty paperboard boxes, play-dough, craft sticks, zip ties, big straws, balsa wood, rubber bands, twine, glue, plastic spoons, pencils, foam shapes, and a lot of dominoes.

Her son Henry was working with Cole Moss of Bowling Green and Addie Patterson of Versailles on a machine that began with one domino hitting a line of dominoes that would knock over three lines of dominoes that would trigger a car armed with thumbtacks to shoot off a ramp and pop a balloon filled with paint that would decorate a piece of paper. Cole commented that his favorite part of the activity was “working with my team.”

That attitude doesn’t surprise Torri, who says one of the biggest challenges is “how long to let them go. They’re all very engaged and keep asking for more time.” After this project, however, there are more fun ones ahead: students will work in pairs to create marble inclines and then individually to invent catapults. Torri also makes sure that the work is focused: “for the first day of this project, some teams skipped over making a plan and a list of materials, so on the second day I had them reflect at the beginning of class and write about what they were doing and what they could do to fix what wasn’t working.”

Ultimately, after viewing gifted education from multiple perspectives, Torri sees it as essential to education as a whole: “Gifted kids come in every flavor, just like every other child, and there’s no one packaged thing we can do that will instantly help all of them. We are told as educators that the conversation about gifted education is not as important as talking about thing like achievement gaps, and we tell parents that their gifted children will be fine no matter what, but being in this graduate program has allowed me to say, ‘No, talking about giftedness is equally valid, and in addressing it you address those other concerns as well because the practices that you do with gifted students also serve students in priority schools really well.’ Why wouldn’t you do something that works for everybody? I don’t feel like I’m a gifted education teacher — I feel like I’m a teacher who’s trying to make sure that whether you are twice-exceptional or gifted or behind or right in the middle, we can figure out ways to make you and everybody else successful.”

Henry, for his part, thinks his mom is doing a great job as a SCATS teacher: “She knows how to relate to kids, and she can make fun lesson plans. She makes what we’re doing even more fun.”