By Erika Solberg

Teaching gifted middle school students is not about simply presenting them with high school-level material or instructing at a fast pace; a classroom of gifted students contains a variety of learning styles, interests, and personalities that require teachers with flexibility, creativity, and confidence. Fortunately, SCATS educators are prepared and eager for the challenge.

SCATS began in 1983 as a way to offer a practicum for WKU graduate students working toward an endorsement in gifted and talented education. This year 18 SCATS instructors are working towards either an endorsement or a master’s degree in gifted education and talent development. For two of those teachers, Stephanie Gahafer and Shelby Fisher, the camp has been a time to push themselves as teachers and to revel in their students’ enthusiasm for learning.

Stephanie just completed her third year of teaching at Plano Elementary School in the Warren County School District. She chose to further her education in gifted studies because she works with students at all ability levels and wanted to do graduate work in an area that she can apply in multiple situations, rather than a single subject. Her SCATS class, Government and Economics, which she says “could also be called World Domination 101,” focuses on different types of government and economies. Her students, in teams or individually, are creating their own countries complete with a constitution, budget, capitol city, map, and flag. The course culminates with a game where the countries compete against each other for control of the world.

The biggest challenge Stephanie has faced involved planning. “When I made my lesson plans, I didn’t know my students,” she said. “After I read their pre-assessments I knew I was going to have to re-examine my plans because they knew more than I thought they would. I’ve been planning off of their lead. I go with their interests and passions and have designed my instruction based with them in mind.”

By the end of the first week, as students started creating their countries, it was clear that she had tapped into those interests. Some teams kept the name of the geographic region assigned to them, like Denmark and Croatia, while others chose their own names such as Terrasen and The Democratic Republic of Veena. Some teams focused their city plans on the basics like schools, a capitol building, and a mall, while one team modeled its city after the layout of Brasília.

Students also had to make other, more significant, decisions. Kareena Pansuria from Bowling Green explained, “I’m doing my country’s budget, and right now I’m calculating the income tax — that’s how I’m going to know how much money I have to spend on education and military,” she said. “I know I want to be a constitutional monarchy, and I think I’m going to spend lots of money on military because it seems like some countries want to bomb everybody.”

Meanwhile, Ryker Williams of Borden, Indiana, was strategizing. “I have a secret plan,” he revealed. “My country’s main’s export is zinc, so I’m going to block the other countries from getting zinc, and when all their people don’t have sunscreen and are dying of skin cancer, they’ll have to come to me and spend money to get zinc.”

Stephanie has been happy with the progress of her course. “What I’ve been most impressed with is their ability to think about concepts abstractly and in new and profound ways,” she said. “I’m excited to see their individuality continue to flourish and to challenge them with real-world problem solving scenarios.”

On Tuesday of the second week, the students finished their initial planning for their countries. Asked what was most important thing when designing their country, Malika Smith of Frankfort said, “Making sure we have a good budget for everything. Making sure our constitution is fair.” Her teammate Eliza Scoggin of Midway added, “And making sure our people are happy so they want to stay with us.”

Their countries ready, the students started to compete. After 10 minutes in which they could form alliances and make treaties with each other, Stephanie presented them with various situations designed to target weaknesses their countries might have. She explained to the class, “It’s not the weaknesses but how you respond to those weaknesses that matters.” She assessed their responses as good or bad; too many bad responses resulted in a fine, and less money in a country’s coffers made it more vulnerable to attacks from the outside.

The first situation Stephanie presented said, “Examine how you tax. Citizens above a 40% tax rate are outraged and threaten to withhold funds. How do you respond?”

One country responded by saying it would lower its top tax rate of 40% to 30%, while another country held firm and said its citizens would face penalties for nonpayment. After the round ended, the class discussed their decisions and debated the benefits of a tiered versus a flat tax system. “You have to think about how your decisions affect people on a day-to-day basis,” Stephanie reminded them. “We’ve learned that when people aren’t happy, they revolt, so people’s happiness affects how the country is doing.”

Overall, Stephanie’s goals for her SCATS class are very different than they would be in her regular classroom. “Teaching at SCATS is unique in that I don’t have to get a certain number of standards or lessons completed within the time frame,” she explained. “My goal for myself is to continue planning my instruction based on the interests and values of my students. If we don’t have time to complete an activity, it’s OK as long as they are actively engaged in minds-on learning. I want to continue giving them time to discuss and learn through each other.” Her students’ focused, excited participation in the world domination game suggests she is meeting her goals.

Shelby Fisher also teaches to her students’ interests. An eighth grade science at Bazzell Middle School in the Allen County School District, her brother and nephew are gifted, so she has a particular passion for the field of gifted studies. “I felt a lot of those students don’t get those service that they need within the regular classroom,” she said. “As an undergrad, I was never trained to teach gifted students.”

Her course, From Mars to Mutations, allows students to explore various science and engineering problems using tiny programmable robots called Ozobots. In the first week, students used the Ozobots to map and later mutate the DNA of an imaginary superbug, and in the second week their major project involved calculating how to maneuver a rocket from Earth to rendezvous with a satellite traveling around Mars, a simulation based on the movie “The Martian.” Shelby believes these lessons are ideal for gifted students. “They have to make a plan, and when it doesn’t work they have to plan again,” she said. “Working through that thinking process is such an important skill for all kids to learn, and gifted kids especially need that challenge to continue to think and engage in practices that are like what scientists do in the real world.”

The students began their work with the Ozobots and DNA by learning how to use the robots. Then they observed how the Ozobots’ behavior changed when traveling on lines drawn using different colored markers. For example, one color pattern made the Ozobot spin, another made it blink white, and another made it zigzag. The students worked in partners, with Shelby moving from group to group helping them troubleshoot and strategize. One student, excited by his discovery, exclaimed, “Red-green-blue slows it down, and blue-green-red speeds it up. That’s so cool!” The class later assigned certain Ozobot behaviors to base pairs of nucleotides in order to map their superbug, named Ozopox. Then, after a mini-lesson on types of genetic mutation and the effects those mutations can have on organisms, the students worked to mutate the Ozopox.

On Friday, Logan Stewart of La Grange explained the process he had worked through “This is the last mutation I did,” he said. “It started out as AGCT, which is a nucleotide code, and then I did elimination to get rid of the C and turn it into AGT. Before I mutated it, the Ozobot did a back walk, and then after it did a snail dance.”

Chloe Harper of Allensville said she liked the uniqueness of the project. “We got to create own DNA sequence,” she said. “Now I know about the types of mutations — we didn’t learn that in school.”

The DNA project went well, Shelby felt. “One thing that surprised me was the depth and complexity of conversations students had with each other,” she said. “I also found it interesting how they always question the learning they are doing. For example, when exploring Ozobot behaviors, many students asked, ‘What would happen if…’ Students also asked a lot about the various diseases and traits that are caused by mutations. While this type of thinking and discussion occurs in my regular classroom, in this setting there are 16 students who are all thinking and questioning at more in-depth levels with each other and not necessarily facilitated by me.”

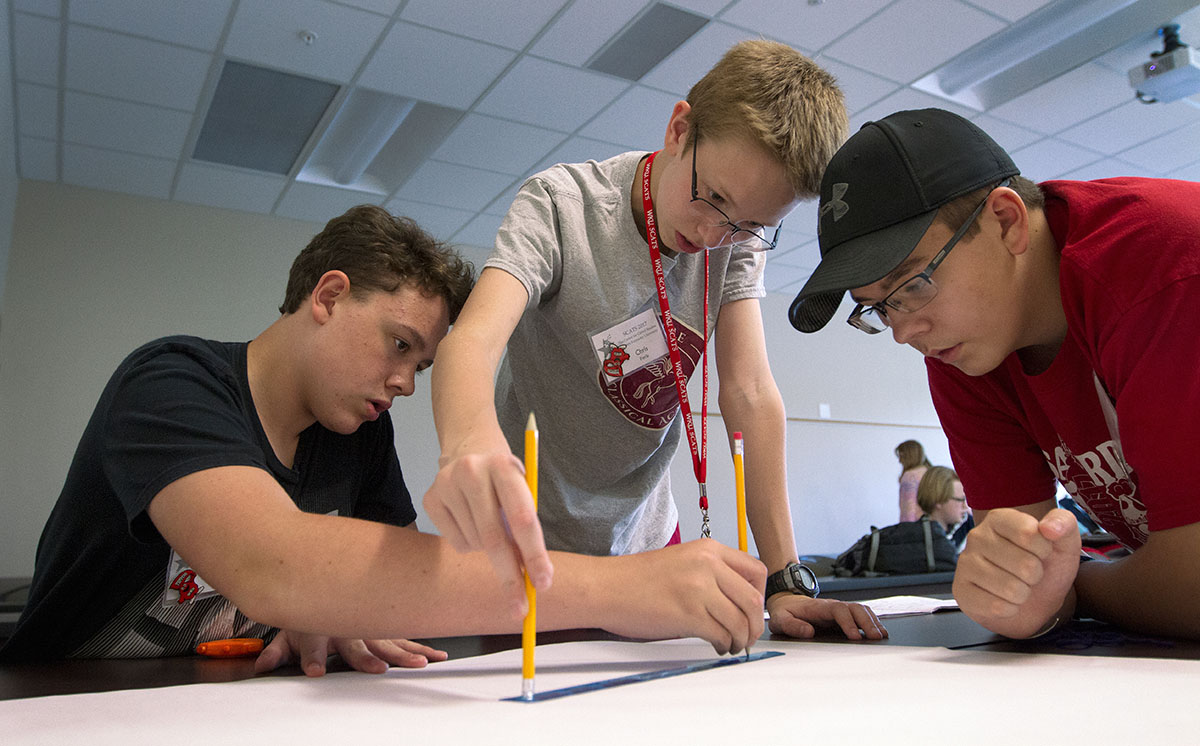

In the second week, Shelby presented the students with their new challenge: figure out how to get two Ozobots — one traveling in a circle 50 centimeters in diameter, and a second traveling down a seven meter line at a slow and then fast speed — to arrive at the same spot at the same time. To complicate matters, students could only use one Ozobot at a time when making their calculations. Shelby expected students to have to try multiple times before succeeding. “We’re going for engineering design practice and scientific thinking,” she said.

As students knelt on the floor over long strips of register tape with black lines, or huddled at desks around big pieces of paper with circles drawn on them, Shelby heard a lot of adjusting, modifying, and sharing. Sydney Petrie of Louisville said the hardest part was “working with the different lengths because one is so much longer.” For Neo Nathoo of Bowling Green and W.P. Hurt of Edmonton, the biggest challenge was writing out the plan.

At the end of class, with each group at a different point of the project, Shelby asked them to write in their notebooks reflecting on their experiences so far and what their next steps would be. This process puts their thinking to paper, she explained. “It ties up their work so they think about what they’ve done and how to improve and be better,” she said. In other words, they get to see learning and problem solving as a continuous process: it is not just about getting the right answer, a task that many gifted students have mastered, but thinking about how to got there.